End of The Five Day Workweek?

Many Americans still aren’t going back to the office even though other sector activity has picked up. According to data from Kastle Systems, office attendance is at just 33 percent of its pre-pandemic average. For tens of millions of knowledge-economy workers, the office is never coming all the way back.

Tech, media, and finance companies have basically stopped talking about their full return-to-office plans. “I talk to hundreds of companies about remote work, and 95 percent of them now say they’re going hybrid, while the other 5 percent are going full remote,” said Nick Bloom, an economics professor at Stanford University. After two years of working from home, employees don’t just prefer it. They also feel like they’re getting better at it. Despite widespread reports of burnout, self-reported productivity has increased steadily in the past year, according to his research.

Not every city is facing the same level of office abandonment. Occupancy rates in Houston, Austin, and Dallas have substantially and consistently outpaced those of coastal cities like New York and San Francisco. One plausible explanation is that remote work is partially sustained by COVID caution, and southern cities have a more laissez-faire attitude toward the pandemic than the bluest of the blue metros.

The majority of Americans still cannot and do not work remotely. But Bloom has identified at least three major implications of this long-term shift in office work:

1. The five-day workweek is dying.

According to Bloom’s research, the most popular model of hybrid work has employees in the office Tuesday through Thursday. “This model, with Friday through Monday out of office, is hugely attractive to new hires, and it’s become a key weapon for companies,” he said. “It’s not that everybody gets a four-day weekend, but rather it gives them flexibility to travel on Fridays and Mondays, while continuing to work.” Add it up—three days in the office for tech and media workers; four days in-person for hospital staff—and the five-day workweek seems endangered. Bloom suggested that schools might respond to these changes by offering teachers Monday or Friday off, which could be the nail in the coffin of the old-fashioned workweek.

2. The age of hybrid work is going to be a beautiful mess.

When the internet disrupted brick-and-mortar stores, the response from many retailers was: Make shopping an experience. Now the internet has disrupted brick-and-mortar offices, and the response from companies may be similar: Make the office an experience. "The one great advantage of the office is that it meets our tremendous desire for human contact,” Mitchell Moss, a professor of urban policy and planning at New York University, told me. If people are going to come back to the office multiple days a week, Moss said, the office will have to adapt. “Successful new offices will be like vertical yachts,” he said, “an experience that people seek out, with terraces, and outdoor areas, and fancy gyms, and places to eat.”

But return-to-office preferences are all over the place, and any one-size-fits-all policy is going to make a lot of people upset. According to Bloom’s survey data, more than 20 percent of respondents would prefer to work from home “rarely or never,” while more than 30 percent say they would prefer to stay home for the entire workweek. The most popular hybrid solution for employers—three days in the office for everybody—is the preference of just 14 percent of workers.

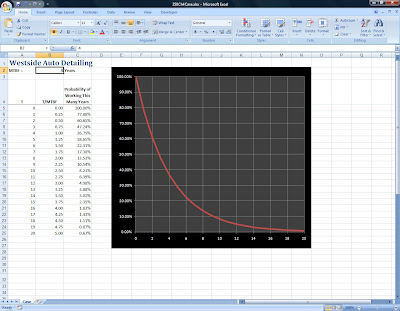

A chart showing responses to the question "How often would you like to have paid work-days at home post-COVID?" The hybrid total seeking at least 1 day a week is 45.3 percent, while 32 percent seek 5 days:

3. Cities are already starting to freak out.

If office occupancy never recovers, downtown areas will experience an extended ice age. Emptier offices will mean fewer lunches at downtown restaurants, fewer happy hours, fewer window shoppers, fewer subway and bus trips, and less work for cleaning, security, and maintenance services. This means weaker downtown economies and less taxable income for cities. For this reason, some of the most outspoken advocates for return-to-office these days aren’t chief executives, but rather politicians and state officials. “Business leaders, tell everybody to come back,” New York Governor Kathy Hochul said earlier this month. “Give them a bonus to burn the Zoom app.” New York City Mayor Eric Adams echoed those remarks. “New York City can’t run from home,” he said. “It’s time to get back to work.”

In New York, Boston, and San Francisco, subway ridership could be permanently depressed. That means that transit authorities might never recover from their pre-pandemic highs, and downtown areas might never recover the lost foot traffic from weekday shoppers. Sarah Feinberg, who served as interim president of the New York City Transit Authority until 2021, said she’s worried not only for the transit authority’s finances but also for the soul of the city. “It is important for offices to reopen and for white-collar workers to start commuting again,” Feinberg said. Remote work might be “good for the individual,” she added, but “we are in a very dark place if the only people who use transit are the people who actually have to show up to work in person, and the only places that make employees show up in person are the places that employ physical labor. That’s not a city I want to live in.”

It is, however, a city that many people want to live in. Rents in the New York area are skyrocketing, as people pour into Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Hoboken. A remote-work New York will not be the same place it was in 2019. Residential neighborhoods will bustle throughout the week, while Wednesdays in Midtown will feel like Sundays in Midtown used to. Some Manhattan offices will transform into apartments, alleviating the island’s housing crisis, while transit presidents will feel pressured to raise ticket prices, sadly punishing the low-income in-person workforce. The point is not that these things are all good or all bad but precisely that they are complicated. Americans really, really don’t want to go back to the office, and we are just beginning to feel the repercussions.